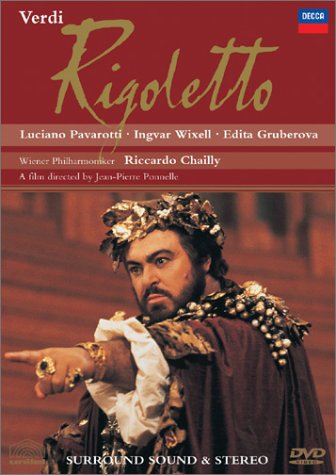

At the ducal court of Mantua, the hunchbacked jester Rigoletto mocks the courtiers cuckolded by the profligate Duke, stirring them to plans of vengeance. Count Monterone appeals to the Duke for the return of his dishonoured daughter, but is cruelly mocked by Rigoletto. Enraged, Monterone calls down a father's curse on the terrified jester.

At the ducal court of Mantua, the hunchbacked jester Rigoletto mocks the courtiers cuckolded by the profligate Duke, stirring them to plans of vengeance. Count Monterone appeals to the Duke for the return of his dishonoured daughter, but is cruelly mocked by Rigoletto. Enraged, Monterone calls down a father's curse on the terrified jester.

Outside his house, Rigoletto encounters Sparafucile, a professional assassin, but has no need of his services. Rigoletto warns his daughter Gilda to remain concealed in their home. She does not reveal to him that she has fallen in love with a handsome young man she has encountered on her way to church. The object of her affections is the Duke, who appears as soon as Rigoletto has left, bribing Gilda's nurse to admit him and to speak well of him to Gilda. He tells her he is a poor student. After he leaves, the courtiers come to abduct Gilda, believing her to be Rigoletto's mistress. They trick Rigoletto into assisting them, assuring him that it is the Countess Ceprano they are abducting from the neighbouring house. When he realizes what has happened, he is distraught. He remembers the curse.

Outside his house, Rigoletto encounters Sparafucile, a professional assassin, but has no need of his services. Rigoletto warns his daughter Gilda to remain concealed in their home. She does not reveal to him that she has fallen in love with a handsome young man she has encountered on her way to church. The object of her affections is the Duke, who appears as soon as Rigoletto has left, bribing Gilda's nurse to admit him and to speak well of him to Gilda. He tells her he is a poor student. After he leaves, the courtiers come to abduct Gilda, believing her to be Rigoletto's mistress. They trick Rigoletto into assisting them, assuring him that it is the Countess Ceprano they are abducting from the neighbouring house. When he realizes what has happened, he is distraught. He remembers the curse.

The courtiers describe their abduction of Gilda to the Duke. He is delighted to discover that she has been brought to his palace and awaits him in his bedroom. Rigoletto now enters, feigning indifference but desperately seeking signs of the whereabouts of his daughter. When he realizes what has happened he first curses, then pleads with the courtiers for her return, but to no avail. Gilda appears en deshabillé, and Rigoletto swears vengeance on the Duke.

The courtiers describe their abduction of Gilda to the Duke. He is delighted to discover that she has been brought to his palace and awaits him in his bedroom. Rigoletto now enters, feigning indifference but desperately seeking signs of the whereabouts of his daughter. When he realizes what has happened he first curses, then pleads with the courtiers for her return, but to no avail. Gilda appears en deshabillé, and Rigoletto swears vengeance on the Duke.

The Duke has been lured to a remote inn by Sparafucile's sister Maddalena. Rigoletto has paid Sparafucile to kill the Duke and to deliver his body in a sack so that he may himself throw it into the Mincio. Rigoletto brings Gilda with him to spy on the inn, hoping to reinforce the notion that the Duke is not a man of honour in affairs of the heart. Gilda is unimpressed.

The Duke has been lured to a remote inn by Sparafucile's sister Maddalena. Rigoletto has paid Sparafucile to kill the Duke and to deliver his body in a sack so that he may himself throw it into the Mincio. Rigoletto brings Gilda with him to spy on the inn, hoping to reinforce the notion that the Duke is not a man of honour in affairs of the heart. Gilda is unimpressed.

Rigoletto sends her home to change into men's clothing for their flight to Verona. Infatuated with the Duke herself, Maddalena begs her brother to spare him and to murder the jester instead. His sense of professional responsibility offended, Sparafucile refuses, but does go so far as to agree that if anyone else should happen to show up at the inn on this wild and stormy night, he will murder them instead. Gilda, returning and hearing all this, sees her chance to help the man she loves. She boldly walks up to the door of the inn, knocks, is admitted and promptly stabbed and stuffed into the sack for Rigoletto. Rigoletto is just about to throw the sack in the river when he hears the Duke still singing in the inn. Wildly he opens the sack to find his dying daughter, who with her last breath assures him that she will pray for him with her mother in heaven. Again, Rigoletto recalls Monterone's curse.

Rigoletto sends her home to change into men's clothing for their flight to Verona. Infatuated with the Duke herself, Maddalena begs her brother to spare him and to murder the jester instead. His sense of professional responsibility offended, Sparafucile refuses, but does go so far as to agree that if anyone else should happen to show up at the inn on this wild and stormy night, he will murder them instead. Gilda, returning and hearing all this, sees her chance to help the man she loves. She boldly walks up to the door of the inn, knocks, is admitted and promptly stabbed and stuffed into the sack for Rigoletto. Rigoletto is just about to throw the sack in the river when he hears the Duke still singing in the inn. Wildly he opens the sack to find his dying daughter, who with her last breath assures him that she will pray for him with her mother in heaven. Again, Rigoletto recalls Monterone's curse.

Reflections of Rigoletto

Or how the hunchback gave his only daughter to die for our sins

Mantua is proud to be the birthplace of Virgil, who posthumously guided Dante through Hell. A modern guide to Mantua may surprise the opera-loving visitor by pointing to the houses of Rigoletto and of Sparafucile. It is evidence that Verdi's Rigoletto is powerful enough to have penetrated the world outside opera in every sense. Tongues may be firmly in Mantovan cheeks as these buildings are pointed out, for the opera-lover knows the characters to be fictional. Any opera dictionary will point to its source in Victor Hugo's Le Roi s'amuse of 1832 and explain how the censors allowed it to be staged with a Mantovan Duke in place of the French King François I. So Hugo's Triboulet, the evil jester, became Rigoletto and his daughter Blanche became Gilda. The story and characters are so strongly drawn as to suspend our disbelief and, if it is horrible, then so are many fairy tales and the setting is usually too remote to be threatening. "Grand Guignol" is the anachronistic description often applied and it is not entirely inappropriate. For the first critic of the Venice première of 1851, it was a "Satanic" piece and he hoped that the composer, having got it out of his system, would now apply his skills to a worthier subject. Yet, far from being an entirely theatrical monster, Rigoletto may, after all, have had a real, if small, human model.

Because we associate them with their moonlit twentieth-century revival, the Commedia dell'arte figures of Columbine, Pantalone and Pulcinella can seem arty indeed. The arte of the name however indicated a low comedy, performed by travelling professional troupes of actors or artisans. The scenarios, many of which survive, were mere outlines and improvisation filled them out with topical humour and business. If tragedy looked back to Greek mysteries and myths, then these comedies could point to their own ancient lines, where heavy fathers, scheming servants and confused identities had been entertaining the crowded amphitheatres for centuries. Young lovers were allowed their own faces, being less set in a humour, but the old men and servants wore masks with hooked noses, beards and high cheekbones.

The masks of comedy depended on immediately recognizable characters while the pseudo-science of physiognomy proposed the reading of an individual face like a palm with each feature contributing hints. The external appearance would be scrutinized for signs of moral delinquency or sexual perversion and it was the prisons and hospitals which furnished the text-books with examples. Paris had taken to the commedia del arte early, finding in it a piquant blend of comedy and pathos but it was hardly to be expected that the spirit of France could express itself fully in the dreamy, wilting Pierrot. It would also take the name of Guignol, a cousin of Mr Punch and make him the patron Saint of a theatre of horror.

When Victor Hugo declared that the theatre must be a church, he was, in one very literal sense, sixty years ahead of his time. A disused chapel in the red-light district of Montmartre was to be the setting for a peculiarly Parisian form of theatre, whose name to this day denotes displays of gratuitous blood and cruelty. It began in 1897 with stories of True Crime, for its first owner was an ex-policeman and it soon became clear that the bloodiest spectacles were the greatest crowd-pleasers. Men were said to have fainted more often than women at the sight of the gougings and disembowellings, if only because they felt duty-bound not to cover their eyes. The Grand Guignol plays, which were without redemptive intent or literary merit, could be compared to the crescendo of violence in which Mr Punch dispatches his baby, his wife, his dog, the doctor, the hangman and the Devil himself. Both repeat the broadest strokes that best please the audience. Rigoletto is a great deal more sophisticated than this and our participation as voyeurs at the feast of rape, murder and sexual perversity is reflected on the stage by the heartless courtiers and, in the final scene, by Rigoletto himself. Although these mirrored behaiviours on the stage serve to implicate the audience, they also magnify the horror of a social setting which offers no defence to the victim.

The notion of a beautiful girl mysteriously sprung from the loins of an outcast figure is very familiar from The Merchant of Venice and The Jew of Malta. In each case the daughter is equated with a miser's hoard, like gold unhealthily kept from circulation. Somehow to involve the outcast figure with the liberation of his own goods appears to be the highest goal in this kind of blood-sport. But is Gilda really Rigoletto's daughter? We have only his word for it. The child may have been foisted on him as a joke by some previous dissolute court. If he does treat her as a daughter, could it be that he is impotent? Her chaperone is happy to be bribed when the Duke craves entry, so we may even wonder if the father-daughter scenario is a special game which Gilda is ready to play for the hunchback. A taste for perverse sex is awakened or deepened by her rape. If she is raped by the Duke. She speaks of a dishonour which implies it.

Whatever happens in the bedroom, she is curiously empowered by something she calls Love and is prepared to dress as a man and be annihilated in a sordid house of assignation for the sake of it. As Rigoletto plans to move on, we sense that it will not be for the first time. Gilda's origin may lie in disguised identities as surely as her fate is to be murdered in travesty. Rounded at both ends in mystery, her life has a sublime uncertainty. The obscure origins of a heroine are conventionally a sign that aristocratic lineage will be revealed in the last act for a good marriage to be possible. There is no such happy ending for Gilda, though she finds her way back into a womb of sorts, in the shape of the sack. Verdi instinctively felt he needed the sack for verisimilitude and it was one of the details he fought for with the censor.

We are so accustomed to operatic heroines being put through their vocal paces in a mixed banquet of arias illustrative of extreme states of mind that to ask for a centre to the personality may seem irrelevant. Can Gilda ever be anything more than a succession of arias and ensembles? We do not ask the same question of the Duke or Rigoletto or Sparafucile as their music covers a range of feelings which delineates a personality. Gilda's supposed rape and self-sacrifice are events which are not fully explored in her music. To a large extent the off-scene rape derives its power from its musical denial in Rigoletto's pretended good-humour and the indifference of the court. This is a scene of genius but it leaves Gilda unsupported in every sense.

Rigoletto, especially clothed in Verdi's sympathetic music, may be the evil creature who fools us all, including his creators. Is it far-fetched to view him as a totally evil and a consummate puppet-master who allows the courtiers to think they have fooled him? His house, guarded by an easily-corrupted chaperone, is a honey-trap he has baited well. Gilda, like many a kept woman may be uncertain of her own identity and happy to play any rôle she is assigned, even daughter to a hunchback, if it pleases him. She is even happier to welcome a potent young man into her garden. Her month-long affair with the Duke may have reduced Rigoletto's own grasp on them both temporarily but showing Gilda how she is being already betrayed may focus her mind on more material matters. If it doesn't, there will be other tools. If Rigoletto's blindfold does not really blind him then the final contents of the sack cannot entirely surprise him. If he is acting throughout, we may, by a diabolical twist, see his apparent despair as laughter and the whole opera as the most diabolical of true comedies.

|

VIEW RIGOLETTO HIGHLIGHTS

VIEW RIGOLETTO HIGHLIGHTS

The Duke has been lured to a remote inn by Sparafucile's sister Maddalena. Rigoletto has paid Sparafucile to kill the Duke and to deliver his body in a sack so that he may himself throw it into the Mincio. Rigoletto brings Gilda with him to spy on the inn, hoping to reinforce the notion that the Duke is not a man of honour in affairs of the heart. Gilda is unimpressed.

The Duke has been lured to a remote inn by Sparafucile's sister Maddalena. Rigoletto has paid Sparafucile to kill the Duke and to deliver his body in a sack so that he may himself throw it into the Mincio. Rigoletto brings Gilda with him to spy on the inn, hoping to reinforce the notion that the Duke is not a man of honour in affairs of the heart. Gilda is unimpressed.

Rigoletto sends her home to change into men's clothing for their flight to Verona. Infatuated with the Duke herself, Maddalena begs her brother to spare him and to murder the jester instead. His sense of professional responsibility offended, Sparafucile refuses, but does go so far as to agree that if anyone else should happen to show up at the inn on this wild and stormy night, he will murder them instead. Gilda, returning and hearing all this, sees her chance to help the man she loves. She boldly walks up to the door of the inn, knocks, is admitted and promptly stabbed and stuffed into the sack for Rigoletto. Rigoletto is just about to throw the sack in the river when he hears the Duke still singing in the inn. Wildly he opens the sack to find his dying daughter, who with her last breath assures him that she will pray for him with her mother in heaven. Again, Rigoletto recalls Monterone's curse.

Rigoletto sends her home to change into men's clothing for their flight to Verona. Infatuated with the Duke herself, Maddalena begs her brother to spare him and to murder the jester instead. His sense of professional responsibility offended, Sparafucile refuses, but does go so far as to agree that if anyone else should happen to show up at the inn on this wild and stormy night, he will murder them instead. Gilda, returning and hearing all this, sees her chance to help the man she loves. She boldly walks up to the door of the inn, knocks, is admitted and promptly stabbed and stuffed into the sack for Rigoletto. Rigoletto is just about to throw the sack in the river when he hears the Duke still singing in the inn. Wildly he opens the sack to find his dying daughter, who with her last breath assures him that she will pray for him with her mother in heaven. Again, Rigoletto recalls Monterone's curse.