|

The Perfect Wagnerite:

A Commentary on the Niblung's Ring

by Bernard Shaw

THE MUSIC OF THE FUTURE

The success of Wagner has been so prodigious that to his dazzled

disciples it seems that the age of what he called "absolute music

must be at an end, and the musical future destined to be an

exclusively Wagnerian one inaugurated at Bayreuth. All great

geniuses produce this illusion. Wagner did not begin a movement:

he consummated it. He was the summit of the nineteenth century

school of dramatic music in the same sense as Mozart was the

summit (the word is Gounod's) of the eighteenth century school.

And those who attempt to carry on his Bayreuth tradition will

assuredly share the fate of the forgotten purveyors of

second-hand Mozart a hundred years ago. As to the expected

supersession of absolute music, it is sufficient to point to the

fact that Germany produced two absolute musicians of the first

class during Wagner's lifetime: one, the greatly gifted Goetz,

who died young; the other, Brahms, whose absolute musical

endowment was as extraordinary as his thought was commonplace.

Wagner had for him the contempt of the original thinker for the

man of second-hand ideas, and of the strenuously dramatic

musician for mere brute musical faculty; but though his contempt

was perhaps deserved by the Triumphlieds, and Schicksalslieds,

and Elegies and Requiems in which Brahms took his brains so

seriously, nobody can listen to Brahms' natural utterance of the

richest absolute music, especially in his chamber compositions,

without rejoicing in his amazing gift. A reaction to absolute

music, starting partly from Brahms, and partly from such revivals

of medieval music as those of De Lange in Holland and Mr. Arnold

Dolmetsch in England, is both likely and promising; whereas there

is no more hope in attempts to out-Wagner Wagner in music drama

than there was in the old attempts--or for the matter of that,

the new ones--to make Handel the starting point of a great school

of oratorio.

BAYREUTH

When the Bayreuth Festival Playhouse was at last completed, and

opened in 1876 with the first performance of The Ring, European

society was compelled to admit that Wagner was "a success."

Royal personages, detesting his music, sat out the performances

in the row of boxes set apart for princes. They all complimented

him on the astonishing "push" with which, in the teeth of all

obstacles, he had turned a fabulous and visionary project into a

concrete commercial reality, patronized by the public at a pound

a head. It is as well to know that these congratulations had no

other effect upon Wagner than to open his eyes to the fact that

the Bayreuth experiment, as an attempt to evade the ordinary

social and commercial conditions of theatrical enterprise, was a

failure. His own account of it contrasts the reality with his

intentions in a vein which would be bitter if it were not so

humorous. The precautions taken to keep the seats out of the

hands of the frivolous public and in the hands of earnest

disciples, banded together in little Wagner Societies throughout

Europe, had ended in their forestalling by ticket speculators and

their sale to just the sort of idle globe-trotting tourists

against whom the temple was to have been strictly closed. The

money, supposed to be contributed by the faithful, was begged by

energetic subscription-hunting ladies from people who must have

had the most grotesque misconceptions of the composer's aims--

among others, the Khedive of Egypt and the Sultan of Turkey!

The only change that has occurred since then is that

subscriptions are no longer needed; for the Festival Playhouse

apparently pays its own way now, and is commercially on the same

footing as any other theatre. The only qualification required

from the visitor is money. A Londoner spends twenty pounds on a

visit: a native Bayreuther spends one pound. In either case "the

Folk," on whose behalf Wagner turned out in 1849, are effectually

excluded; and the Festival Playhouse must therefore be classed as

infinitely less Wagnerian in its character than Hampton Court

Palace. Nobody knew this better than Wagner; and nothing can be

further off the mark than to chatter about Bayreuth as if it had

succeeded in escaping from the conditions of our modern

civilization any more than the Grand Opera in Paris or London.

Within these conditions, however, it effected a new departure in

that excellent German institution, the summer theatre. Unlike our

opera houses, which are constructed so that the audience may

present a splendid pageant to the delighted manager, it is

designed to secure an uninterrupted view of the stage, and an

undisturbed hearing of the music, to the audience. The dramatic

purpose of the performances is taken with entire and elaborate

seriousness as the sole purpose of them; and the management is

jealous for the reputation of Wagner. The commercial success

which has followed this policy shows that the public wants summer

theatresof the highest class. There is no reason why the

experiment should not be tried in England. If our enthusiasm for

Handel can support Handel Festivals, laughably dull, stupid and

anti-Handelian as these choral monstrosities are, as well as

annual provincial festivals on the same model, there is no

likelihood of a Wagner Festival failing. Suppose, for instance, a

Wagner theatre were built at Hampton Court or on Richmond Hill,

not to say Margate pier, so that we could have a delightful

summer evening holiday, Bayreuth fashion, passing the hours

between the acts in the park or ontheriver before sunset, is it

seriously contended that there would be any lack of visitors? If

a little of the money that is wasted on grand stands, Eiffel

towers, and dismal Halls by the Sea, all as much tied to brief

annual seasons as Bayreuth, were applied in this way, the profit

would be far more certain and the social utility prodigiously

greater. Any English enthusiasm for Bayreuth that does not take

the form of clamor for a Festival Playhouse in England may be set

aside as mere pilgrimage mania.

Those who go to Bayreuth never repent it, although the

performances there are often far from delectable. The singing is

sometimes tolerable, and some times abominable. Some of the

singers are mere animated beer casks, too lazy and conceited to

practise the self-control and physical training that is expected

as a matter of course from an acrobat, a jockey or a pugilist.

The women's dresses are prudish and absurd. It is true that

Kundry no longer wears an early Victorian ball dress with

"ruchings," and that Fresh has been provided with a quaintly

modish copy of the flowered gown of Spring in Botticelli's famous

picture; but the mailclad Brynhild still climbs the mountains

with her legs carefully hidden in a long white skirt, and looks

so exactly like Mrs. Leo Hunter as Minerva that it is quite

impossible to feel a ray of illusion whilst looking at her. The

ideal of womanly beauty aimed at reminds Englishmen of the

barmaids of the seventies, when the craze for golden hair was at

its worst. Further, whilst Wagner's stage directions are

sometimes disregarded as unintelligently as at Covent Garden, an

intolerably old-fashioned tradition of half rhetorical, half

historical-pictorial attitude and gesture prevails. The most

striking moments of the drama are conceived as tableaux vivants

with posed models, instead of as passages of action, motion and

life.

I need hardly add that the supernatural powers of control

attributed by credulous pilgrims to Madame Wagner do not exist.

Prima donnas and tenors are as unmanageable at Bayreuth as

anywhere else. Casts are capriciously changed; stage business is

insufficiently rehearsed; the public are compelled to listen to a

Brynhild or Siegfried of fifty when they have carefully arranged

to see one of twenty-five, much as in any ordinary opera house.

Even the conductors upset the arrangements occasionally. On the

other hand, if we leave the vagaries of the stars out of account,

we may safely expect always that in thoroughness of preparation

of the chief work of the season, in strenuous artistic

pretentiousness, in pious conviction that the work is of such

enormous importance as to be worth doing well at all costs, the

Bayreuth performances will deserve their reputation. The band is

placed out of sight of the audience, with the more formidable

instruments beneath the stage, so that the singers have not to

sing THROUGH the brass. The effect is quite perfect.

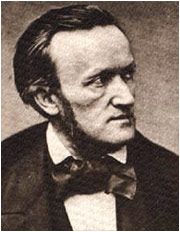

The

greatest composer of German opera, Richard Wagner, b. Leipzig,

May 22, 1813, was the youngest of nine children of Friedrich

and Johanna Wagner. His father, a police registrar, died 6

months after Wagner was born, and his mother was remarried

the following year to Ludwig Geyer, an actor and portrait

painter, who moved the family to Dresden.

Geyer

died in 1821, and in 1827 the family returned to Leipzig.

Wagner was attracted to the theatre at an early age.

His

formal music training was brief - about 6 months in 1831-32 with

the Leipzig cantor C.T. Weinlig. During the 1830s, Wagner held

a series of conducting posts with small theatrical companies, and

he wrote two operas, Die Feen (The Fairies, 1834) and Das

Liebesverbot (Forbidden Love; after Shakespeare's Measure for

Measure); His third opera, Rienzi, was conceived on a larger

scale, and Wagner travelled to Paris in 1839 with the futile hope

of having it performed there. Rienzi was finally accepted for performance

in Dresden in 1842. Its success, coupled with that of Der fliegende

Holländer (The Flying Dutchman) the following year, led

to Wagner's appointment to an official conducting post in Dresden.

His

formal music training was brief - about 6 months in 1831-32 with

the Leipzig cantor C.T. Weinlig. During the 1830s, Wagner held

a series of conducting posts with small theatrical companies, and

he wrote two operas, Die Feen (The Fairies, 1834) and Das

Liebesverbot (Forbidden Love; after Shakespeare's Measure for

Measure); His third opera, Rienzi, was conceived on a larger

scale, and Wagner travelled to Paris in 1839 with the futile hope

of having it performed there. Rienzi was finally accepted for performance

in Dresden in 1842. Its success, coupled with that of Der fliegende

Holländer (The Flying Dutchman) the following year, led

to Wagner's appointment to an official conducting post in Dresden.

There

he completed Tannhäuser (1845) and Lohengrin

(1848). This period of success ended in 1849, however, when his

participation in revolutionary political activities forced him to

flee to Switzerland. Wagner's exile from Germany, which lasted until

1860, marks the start of a new period in his career.

Wagner

began composing the non-conventional opera-cycle Der Ring des

Nibelungen (THE RING OF THE NIBELUNG) in 1848 and did not finish

until 1874.

Wagner

began composing the non-conventional opera-cycle Der Ring des

Nibelungen (THE RING OF THE NIBELUNG) in 1848 and did not finish

until 1874.

The

last great turning point in Wagner's fortunes occurred in

1864 when he was called to Munich by the eccentric young king

of Bavaria, Ludwig II, an ardent admirer of his works and

theories. Ludwig's patronage continued for the last 20 years

of Wagner's life, making possible the performance of all his

mature works and eventually the construction in Bayreuth of

a theatre of Wagner's own design. It was opened in 1876 with

the first complete production of the Ring. Bayreuth soon became

the centre for the promotion of Wagner's works and ideology.

His last opera, Parsifal, was performed in 1882, with

the ceremony normally accorded only to a religious event.

Following

Wagner's death on Feb. 13, 1883, control of the Bayreuth festival

passed to his second wife, Cosima (a daughter of Franz Liszt), and

later to their children and grandchildren, a succession that has

continued to the present.

The

use of legendary sources and the gradual reduction in contrast between

aria and recitative in these operas anticipate the new music drama

that Wagner was to propose in the treatises written about 1850.

The guiding principles of his theory were naturalism and dramatic

truth, which he felt had been compromised by the musical conventions

of contemporary opera.

He advocated a new synthesis of music, verse, and staging

- what he called a Gesamtkunstwerk. The verse, which

Wagner always wrote himself, was to be compressed, metrically

free, and alliterative, dispensing with the end-rhyme that

led to closed musical structures. The open-ended melody of

the vocal line was to be supported by a symphonic accompaniment,

continuously fluctuating with the sense of the text and unified

by a web of motifs associated more or less directly with characters,

things, ideas, or events.

He advocated a new synthesis of music, verse, and staging

- what he called a Gesamtkunstwerk. The verse, which

Wagner always wrote himself, was to be compressed, metrically

free, and alliterative, dispensing with the end-rhyme that

led to closed musical structures. The open-ended melody of

the vocal line was to be supported by a symphonic accompaniment,

continuously fluctuating with the sense of the text and unified

by a web of motifs associated more or less directly with characters,

things, ideas, or events.

Wagner

called these motifs Grundthemen, but they have become better

known as leitmotifs ("leading motifs").

This

theoretical music drama was exemplified in its purest form in "Der

Ring des Nibelungen".

|

Download full version of Ring movie

Download full version of Ring movie